Brooke Kaveney is a research fellow currently involved in an international project, helping to fund alternative solutions to rice production in the saline soils of Southern Vietnam, where local farmers are grappling with the impacts of climate change.

Brooke’s passion for agriculture runs deep. She was raised on a mixed farming enterprise outside Thuddungra, northwest of Young in New South Wales. The Kaveney family run sheep and grow wheat, barley, canola and lucerne on rotation.

Brooke says she owes a lot to her country upbringing.

“I couldn’t imagine growing up anywhere else, being a farm kid was awesome! We were all heavily involved in the farm from an early age, driving machinery, headers, and trucks. If you wanted to learn something on the farm, there was every opportunity to do so. It instilled a desire in us to understand and improve the land that we live and work on,” said Brooke.

Now living in Wagga Wagga NSW, Brooke is still somewhat involved with the family farm.

“My siblings and I usually all head home for harvest to help out. We try and get back there as much as we can. It’s awesome working alongside your family. Sharing the ups and down’s together is special,” said Brooke.

After Brooke finished school, she was accepted into a Bachelor of Biomedical Science, but after taking some time off to travel, she realised it wasn’t for her.

“Someone suggested I follow my obvious passion for agriculture…it had never really occurred to me that there was a career outside of farming. At that point in my life, I wanted to go out and expand my horizon, so I enrolled in a Bachelor of Agriculture Science.”

Brooke then pursued her Honours and spent a year in Vietnam working with local farmers.

“One thing led to another, I did a PhD in soil biochemistry and then fell into my current research program which is funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.”

Brooke is now considered a foreign aid worker. She works closely with research institutions and farmers along the Mekong River Delta in Vietnam, where rising sea levels, tidal fluctuations and drought are leading to saline intrusion in rice producing areas. Essentially, the salt water is killing the rice crops. The international research team is working to identify alternative crops that can be grown to give farmers options to supplement the loss of their rice income, as part of a five-year project.

“Rice is a staple food for the Vietnamese and is a big commodity, with Vietnam being the fifth largest rice producing country in the world, and a net exporter. We’re trying to work with farmers to find out what crops they can grow to create incomes and livelihoods for their families. It’s what makes you feel warm and fuzzy at night. You go to bed knowing you’re helping entire communities rather than just an individual farmer that may have a yield increase in Australia.”

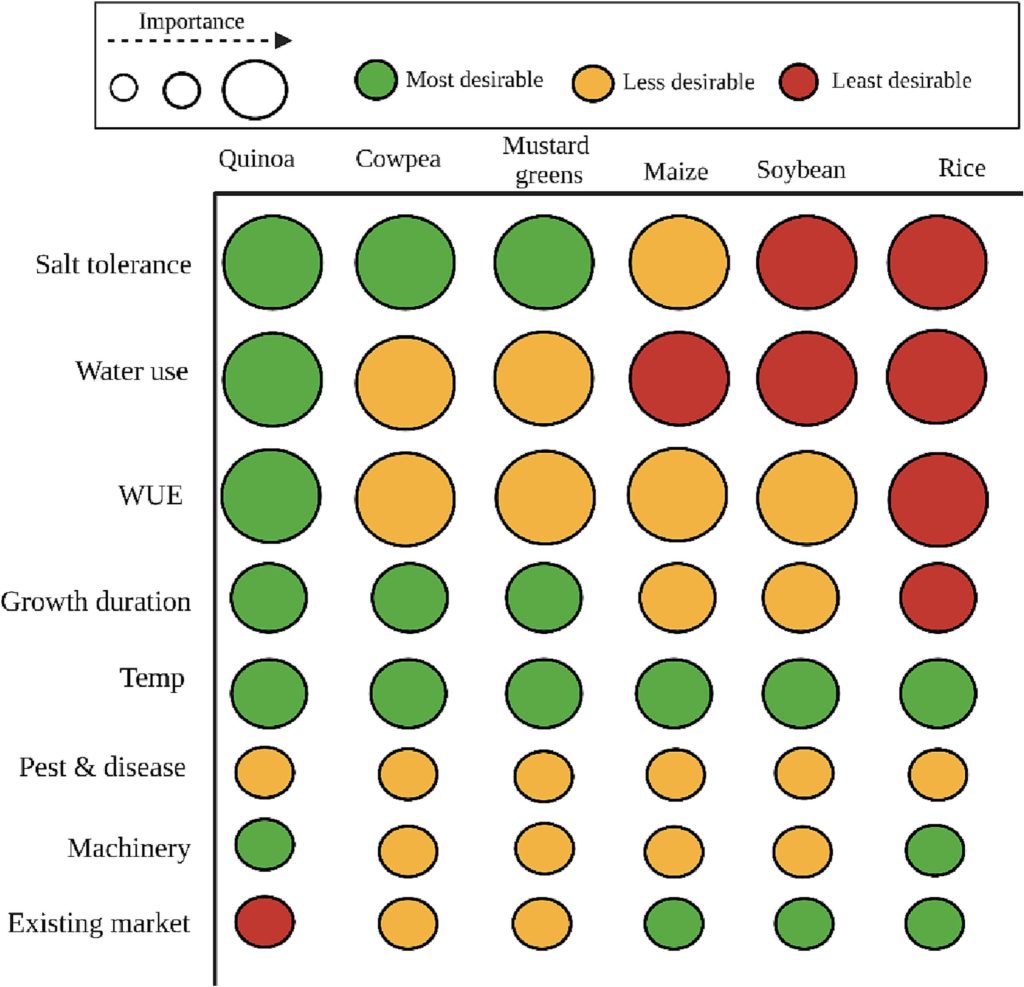

The multidisciplinary team must take into account a range of factors, like whether the crops can tolerate drought given the water scarcity and changing rainfall patterns, whether local people would be willing to consume the crop, if they have access to the machinery needed to harvest the crop, if there are markets available and how it would affect the gender dynamics of the communities.

“Women have important roles in rice farming and if we take that away, where does that leave them? We need to consider how we can educate or train them to ensure they aren’t left behind in the transition.”

Glasshouse trials of alternative crops have begun, with quinoa, cow pea (a green bean like legume), mustard greens, soybean and maize put to the test. The teams are investigating how they can optimise their growth through mulching or irrigation practices to maximise productivity in the harsh land.

source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308521X23000379

Brooke visits Vietnam regularly and is on a first name basis with the local farmers and local government representatives from the equivalent of our Department of Primary Industries.

“We have a very hands-on approach. We visit them in their homes and have dinner and beers with them. That’s the way it has to be, otherwise the project won’t be successful. The changes wouldn’t be implemented once we leave, if we didn’t have that great relationship.”

It’s no surprise that advancements in technology play a huge role in the success of the project, and one simple device is being described as a game changer.

The chameleon soil moisture device is a tool that visually notifies farmers of their crops soil water levels using a colour system, to help them make decisions to boost their crop yields.

When the sensor is in the ground and flashes blue, it means ‘no soil irrigation is needed for some time,’ when it flashes green it means ‘do not irrigate and monitor the situation,’ and red means ‘irrigation is required.’

It comes as farmers in developing nations are prone to over-watering due to a lack of access to advanced soil water probes.

“We found that farmers were wasting all this water and then they’d run out of fresh water and have to start irrigating with salt water, which is problematic.”

Richard Stirzaker from CSIRO developed the device and Brooke says it’s been revolutionary in their work.

“They were originally created for farmers in Tanzania and South Africa and now we import them from Australia to Vietnam to teach our farmers about irrigation efficiency. The colour system is incredible, because it doesn’t matter if you speak Vietnamese or English, it’s universally accessible. These devices have helped us save 50% more water and 25% in labour and fuel in irrigation pumps, without comprising the yield of our crops. They’re affordable too, and cost around $180AUD. By the end of the season, we’re finding our farmers don’t rely on the tool anymore as they’ve been able to educate themselves about water use.”

Brooke says now is the time for collaboration, with low-lying coastal areas increasingly facing climate related issues.

“It’s quite confronting when you look at the literature about forecasts and predictions. By 2050 it’s expected that hundreds of thousands of people will be displaced from their homes in Vietnam in the Delta. It’s a similar story in Bangladesh and Pakistan. We need to collaborate and share information and resources to scale this work up.”

Brooke’s favourite part about the agriculture industry is the powerful sense of community and mateship.

“It only takes a local bushfire or broken-down machinery with rain on the way to see how quickly neighbours come together to help out.”

If Brooke had to give one piece of advice to someone starting out in the industry, she would tell them to keep an open mind.

“I think you shouldn’t narrow your vision too much because the sector is so diverse and you never want to be too blinded by what you think you should be doing, that you miss out on incredible opportunities. When I finished school, I didn’t even know foreign aid in the agriculture sector existed. I was hell bent on becoming an agronomist.”

“Be open and willing to take risks!”